Pacific Drive

Should you play Pacific Drive? If driving a shitty armored car that you made through an irradiated wasteland interests you, your time is probably better spent playing the game than reading this.

This isn't a review, but a dissection. I’m going to spoil (by some definitions) the events of the game, because I will discuss its contents. I will keep out most details because it usually isn’t important, but I will talk about the contents of the game, so…

Rain Dancing on the Windshield

Do you have positive memories of stressful moments? Are there glances with death that you look back to fondly, either due to their value to as story material, or are linked to other things that were happening in your life?

I do. I have a genre of them, in fact. They can be described as "trying to outrun a storm with a vehicle."

I think everyone of driving age in the midwestern US has some version of them. Storms come in all shapes and sizes, with and without warning, and do not discriminate. I have been chased by tornadoes on my bike, I have driven through every sort of ice storms with cars that really shouldn't be in such storms, I have been stranded in floods and hailstorms by fuckheads who take cover on underpasses (don't do this, not only is it unsafe, but you doom your firstborn to be a social media personality).

These moments are, undeniably, stressful. But... my memory of them is watching the sky, seeing the inevitability wash over me, and everyone. Watching the streaks of rain dance over my glass shields, glad that I'm still in some kind of shelter instead of none. The situation devolves from "I need to get home" to "I need to find shelter" to "I need to focus on seeing the road." I have enough experience in doing this that I'm actually pretty good at it. Is this how thrill seekers feel when they are also doing something dumb?

When Pacific Drive announced itself (I think I saw it at either the game awards or state of play) with its now famous trailer, a video that begins with the blare of a tornado-ish siren and an over-the-radio announcement that the area is fucked, you need to leave; that got my attention. An experience I have sort of lived through myself, made digital as a form of entertainment product, that I can turn on and off without the risk of dying, you bet your ass I was going to track this one closely.

Another personal fantasy of mine is driving a hyper specialized vehicle that I have complete control over to modify, customize, and be responsible for (I've got my eyes on you, Caravan SandWitch). The trailer briefly hints at this with a quick swap-cut to the station wagon having been modified to a sci-fi monstrosity. I will play this game, I resolved.

About a year and a half later, I did.

Pacific Drive

You start the game as a nondescript delivery driver delivering a deliverable to a delivery address it doesn't matter you get literally sucked into the Olympia Exclusion Zone. You are then met with a car, the only working car in 100 square miles (the delivery truck got shredded), and the voices over the radio usher you to a base, which is also a gas station. OK. Great.

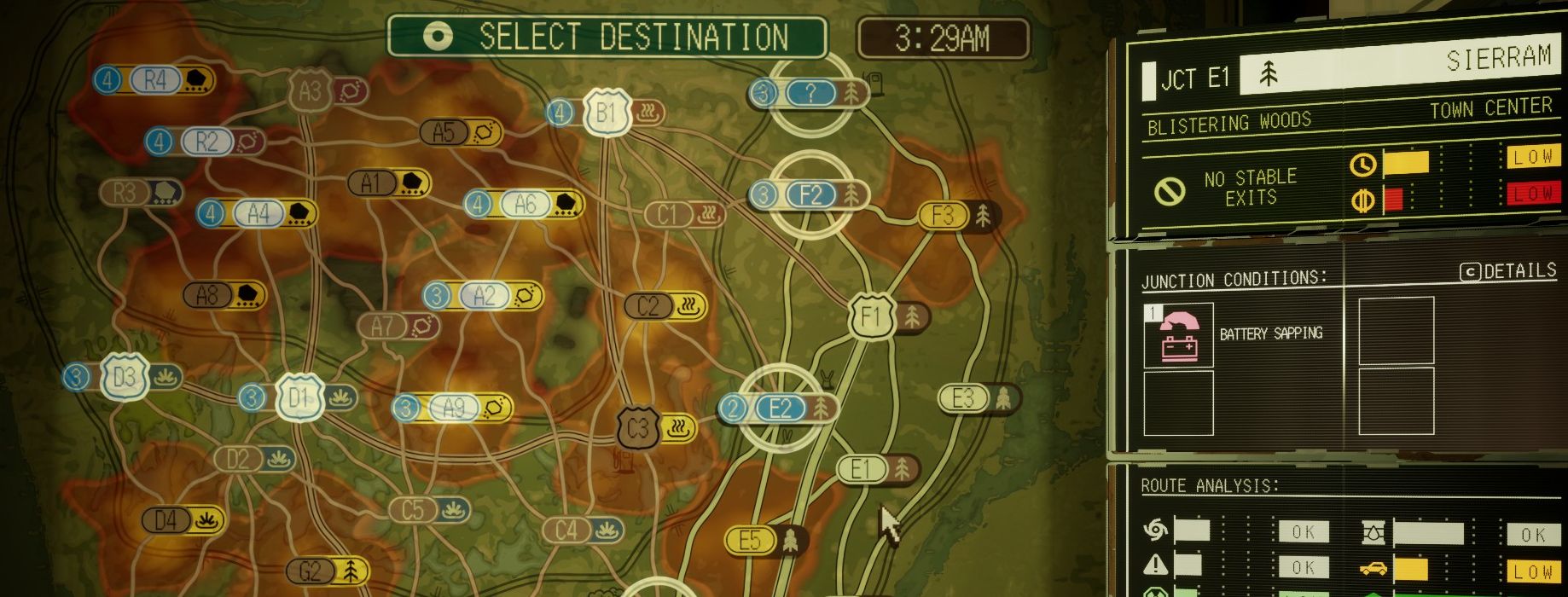

The meta is soon established: You are given a map of the exclusion zone, in which you can choose junctions to aim for or pass through. Each point must neighbor other junctions, and you may never go back in one run. Each junction, with a handful of exceptions, are picked by the game from a dozen random handmade maps. Different areas might change what set they are picked from, and there are a few maps with set locations, but for the most part, you'll start to recognized these areas after a while. The game will sprinkle some anomalies and resources and landmarks on the map, but the roads are what they are.

But how do you get back? Well, that's what the gateway is for. In the passenger seat of your car is a device that can recycle energy from LIM-tech stabilizers scattered around certain junctions. You can yoink the cores of the stabalizers as you pass through for resources, and you might as well, your mere presence will destabalize the region to the point where it is consumed by a terrible storm of energy and radiation. Once you have enough, you can open a gateway that warps you back to the garage.

The catch, is you can't deploy a gateway right next to your car. Oh no. You must be a minimum safe distance from a gateway location for it to open, usually at least a half kilometer away. And once it is open, the storm comes for you immediately, slowly shrinking the safe area that is not simultaneously on fire, electrocuted, and irradiated. If you get to the gateway in one piece, you warp back to the gas station base with all your loot.

The voices on the radio will beckon you to set out into the wasteland to various ends, and... lets talk about that.

Ace Combat, This is Not

When Armored Core 6 came out, a lot of people were introduced to the Radio Play format of story presentation, made originally famous (maybe, I dunno) by the Ace Combat series, specifically 3 on up.

I personally love this sort of thing, it's a very economical form of getting the story in front of the player, it tends to be thematic and diegetic (though, there is an ongoing mystery as to how your character is able to hear enemy radios, but whatever), and it is very economical in terms of assets the devs have to create (no mouth sync, no character animation, no scene blocking...). A lot of games have been exploring the radio play method as a way to get the story across.

However.

There is a slight-of-hand that happens in Ace Combat, Armored Core, etc. The people talking to you are, for the most part, still physically represented in the scene and gameplay. The wingmen yelling about being shot down are usually actually being shot down in Ace Combat, the Mech Assassin yelling threats into your ear is also the one unloading a shotgun your general direction in Armored Core.

Pacific Drive's dialogue, in most cases, isn't said at you, but around you even. You just happen to be on the same frequency, and they figure you are listening. The times they talk to you are actually pretty rare; they know you can't respond but they could have made the relationship lean on that fact more.

A formative childhood memory is driving extreme long distances in a truck with my dad while his car ham-radio auto-skipped through frequencies. You overhear a lot of semi-public conversations this way, the type of things you don't really care to contribute and people don't care that you're listening. Traffic, weather, equipment, current events, that sort of thing.

When I think about this memory in comparison to Pacific Drive, I think a small tweak in the framing could have made this more interesting. This could have worked.

There is a point near the end of the jumping-the-old-wall sequence where a character you have been hearing the entire time dies. He dies hard too, a really rough way to go, and they do it for you... kinda. He does it in service a theory that has been in a logjam for something like 40 years, and it may finally resolve with your presence (and a complicated relationship between the other characters that are otherwise well done). This death was affecting to me, it comes out of the blue, but I also feel the rest of the game fails to capitalize on it. The characters kind of spend the next few missions just unpacking what happened, there is no bigger change to gameplay or the situation for you, it is simply a free-floating event. The presentation lacks the solid reinforcement of what is happening to me as the driver, and the story is somewhat hobbled over it.

If I were tasked with trying to fix this, I would have reworked the presentation of the story slightly so that the characters are observing you for sport. "Whoever this guy is, maybe he'll survive the storm if he finds the lab hidden in the gas station." "Maybe if we send him blueprints, he'll get the idea of exploring this area we have been wondering about." The game flirts with this idea from the beginning but quickly becomes them talking to (then around) the player. The player experiencing the characters go from detached observers to invested fans would hit differently, I feel. When one of them comes out of the blue to die for you, that would be a kick to the gut. Heck, it would add some intrigue if you overheard something they didn’t want you to hear.

The writers had the ability to do this in them. There is an in-universe podcast called "Frequency Files" that manifests as randomly spawning cassette recorders on the map. These episodes are the closest the game comes to explaining what the heck is going on, and I almost died multiple times tracking these tapes down. Shoutout to that one time I drove off a cliff to get to a gateway because the cassette was on the wrong side of a cliff on the wrong side of a storm.

I’m Reading it, but I’m not Seeing It

There is another interesting place where the story overlaps the gameplay in an interesting way: the log entries.

You are encouraged to scan anomalies, basically breaks in reality that want to kill you most of the time, with your head mounted scanner. Easy enough, and you are gated on research by your ability to scan these entities. And…

Let’s take a detour: it’s my belief that games took the wrong lessons from SCP.

If you didn’t know, SCP is a collaborative writing project in the form of a database kept by a morally dubious Foundation known as Secure-Contain-Protect. Each entry has a number, and there are standards for each entry, such as a containment class, risk class, danger class, secrecy rating, and containment procedures, then followed by a description of what is at hand. This presentation style is very pure: it is presented in universe for those that have access to this database and the need to know, so of course it would lead with the really important details first. If an announcement goes over the PA saying 650 is loose and you look up what that is, the entry begins with “You always need to be looking at it, shooting it doesn’t work,” not an event that happened with it 10 years ago.

LIM labs, the instigators of the anomalies in this area of the Pacific NorthWest, was tracking and cataloging the anomalies in a very SCP way, giving them numbers and nicknames. But the entries aren’t that useful.

More than once, I would scan an unholy terror of an anomaly only to get some email someone sent a long time ago about thinking about transferring into another position in LIM labs. That’s cool and all, but I kinda need to know NOW how this thing is going to try and fuck me over (because there are only two anomalies that are non-hostile, and 2 others that are arguably non-hostile). Bonus: going into the scanner interface does not pause, so while I’m quickly reading this log entry the thing could be making its moves on me without me noticing.

The extremely personal nature of a lot of these logs coupled with the fact that there is no pausing in the interface leads me to believe that most of these were intended to be audio logs at one point, but time or money or focus was redirected elsewhere. A shame, I would probably have engaged more if I could have listened to the entries as I hike to the next LIM stabilizer.

There is a more tragic way the logs interact with the game: it hints at a world much more mysterious than the one you interact with. There are logs describing the day the Old Wall fell, when “it” walked over the 100 foot tall concrete and electrified barrier and made everyone within 3 miles panic. There are logs describing actual modern alchemy, sentient materials, and swaths of military personnel going missing. There is talk of a dreaded door that, when opened, opens everything and everyone nearby.

None of these things are in the game, beyond their log entries. While I don’t need to see a mile-high creature in the game, it would have been neat to see hints of the larger machinations. The military at one point had a brigade stationed in the exclusion zone, but at no point do we see any military equipment. We don’t see any giant footprints, nor do we see any signs of the exodus that happened one fateful day.

There is a log entry for Salamanders (an alien material, not the animal), where the writer notes that the animals stay away, and the places where they grow are silent. And yet, I can still hear the buzzing of insects and croaks of frogs whenever I am near them.

Survival Games for Those Who Hate Survival Games

When I went to Abiotic Factor from Pacific Drive is when I realized how much Pacific Drive was spoiling me on inventory management.

A large part of the game is the care and feeding of your station war-wagon. Each chunk of the car is installed and removed as seventeen (17) large discrete pieces mounted to the frame: 5 doors, 5 body panels, 2 bumpers, 1 engine, 4 wheels. Later an additonal 8 pieces become available: 2 passenger seat equipment slots, 4 side mount racks, and two roof rack mounts. Each piece is interchangeable, a "door" part can be any passenger door and the hatchback door as an example.

There is a lot of give and take to this setup: while this is a massive simplification to the parts to an actual car (most cars are more than 26 pieces), at no point is the actual interaction with the car a menu. You hold each piece in your hands (it's too big for your inventory) lug it over where it needs to go, and slot it into the spot where needed. These pieces are lovingly modeled, are physical things you can chuck across the room and pile up, and putting them off and on your car is snappy with an appropriate spark effect and impact driver sound.

That's not to say there aren't menus, but the game does its utmost to minimize your experience with them. While in your garage, the storage within it is your inventory. All you have to worry about is finding a place to store the junk you are hauling back, and it will show up as available for crafting. Combine with the automerge and autotake hotkeys, and you basically don't need to worry about inventory management at all. Later you get an upgrade that makes the storage aspect functionally a quantum inventory, turning the Resident-Evil-Tetris inventory and making it a large infinite list.

When out in the field, many of the conveniences fall away. Your trunk inventory exists separately from the roof inventory, and if you are looking for tools or spare parts, it matters where you look first. But that's fine, I'd rather it be this system than installing the roof storage and magically getting 20 extra squares or whatever.

My only complaint really is the stacking: I don't know how many of each resource goes into a stack. The fact that there are variable stack sizes is the game's compromise to the fact that there is no tracking of weight, that's fine, but there is no way beyond experience to know that there are 5 units of lead to a stack.

Where things get really interesting is car parts. Remember: they're too big for your backpack (which is a limited, upgradeable grid like your car storage but on you), and while you can store extras in your car, they take up a lot of space. But here's the thing:

Occasionally you find wrecks of vehicles, and sometimes, those vehicles have parts. The parts of your cars can wear out and (spoiler) fall off. You eventually can also get a minelayer device that can pop off parts from wrecks you may find, and you may also find loose parts if you are lucky.

These parts are functional, sometimes OK, but usually they are not the super-specialized, LIM-tek'd out parts you built bespoke for your wagon. So: do you use the new(er) part to replace a damaged or missing piece, do you keep it for later but eat the space cost of the massive part? Or, do you do the inadvisable thing and do without, keep the space for loot while missing something protecting you?

To make things even more complicated, parts are usually too big for your backpack. If the part you want is being harrassed by an anomaly, what is your play? Do you toss a flare to distract it? Attack it with your grinder? Grab the piece and run back to the car? How fast do you think you can install thack sucker?

These sorts of questions are what most games would kill for. A lot of games took the wrong lessons from Minecraft, i.e. open-ended worlds with lots of crafting and inventory management and.... look, it works for Minecraft because literally everything in that world is an item that can be used in recipes, and the sheer amount of craftables needs a pretty rough but powerful interface to deal with. But most games don't allow the player to strip-mine for resources, and when the game is about driving or zombies or something, everything needs to be rethought.

Both the directors for Pacific Drive and Abiotic Factor have said in interviews that they do not generally like survival games and were trying to craft a very specific experience, and it shows. Pacific Drive even has a tool in the garage that picks up everything on the floor and puts it in a box. The game wants you driving, and by golly, if it gets in the way, it is minimized.

Not Stock Parts

For a good 70% of the game's runtime, you are the car. A crummy, wood paneled 1960's-ish station wagon. You are forced to drive this thing in first person, and the game will remind you of that when your windows crack and your windshield wipers stop working.

And boy howdy does your car drive like an old station wagon. Tapping the E-Break will fishtail on anything but the most perfect road. The stock engine struggles going up hills, and off-road handling is laughable. The trunk will bop you on the head for 3 points of damage, if you don't watch your head. And when indescribable forces from beyond nature are bearing down on your position you gotta remember to look down, turn on the engine, shift to drive, and then get going.

It is a small mercy that the car has an automatic transmission.

For apologetic narrative reasons, this car is the only car that works, and you are soulbound to it. The game, then, is to find out why and undo it so you may leave.

They didn't need to do this. They let you paint the car in a ton of different ways, customize almost everything about how this car handles, its fuel capacity, its radiation defenses. You can choose ultrabrite alien headlights with a ding to energy consumption, or less bright but cheaper headlights instead. If you get 20 hours into this game without nicknaming your hulking rolling best friend, you probably empathize a little too much with the things trying to steal your headlights.

The game could be over in 15 hours if you don't care about those things or are especially determined. I did not do that. At time of writing, I 'm one of the 3% with the steam achievement where the driver completely upgraded their garage. I died literally once, and that was because of a technicality.

This technicality has two dovetailed parts: the first part is that the game expects you to die a lot more often than I did, and the other is that it lets you commit the most drawn out suicide imaginable.

Tips

You must die once in Pacific Drive to get the last tier of research.

There are a handful of mechanics that only kick in when you die, which is regrettable. An anomaly that must be scanned appears where you died, some dialog only makes sense if you’ve died, there are items that function as extra lives you can slot into the car, it’s a questionable design assumption. I’m playing the survival game to survive, don’t punish me for being good at it.

My other beef is that you are allowed to choose a dead end as a destination on the map. Dead ends do not have the preconditions necessary to create a return gateway, so if you get there you kind of just hang out until you end it yourself or the storm comes and gets you. To the game’s credit, it does ask “Are you sure?”, but to its discredit, it looks like the “Are you ok with this route?” prompt you offhandedly dismiss. Driving 7 junctions to a slow and drawn out death sucks, just don’t let me choose those, you already don’t let me choose routes I wish I could.

Recent Developments

I beat the game in April of this year. It took me about 50 hours, and when I was done I had upgraded my car about as far as it could go. I generally opted to scrap and remake car-parts instead of repairing them as the material to do field repairs is fairly rare, and would reserve those for emergencies. I rolled with armored and acid-proof parts, and stuck a radar and ionizer on the roof. The side slots were, in no order: a rain-to-gas converter, a lightning rod, gas extender, battery extender. The rear seats had extra gas, and extra battery. The bumpers had the various mounted LIM tech devices you get near late game. The tires were LIM and all-terrain tires. I always left with one extra tire, one extra tool each, and some shock rods.

IronWood has since added more features to the game since I played. They have added ways to customize the game to your exact parameters, down to the physics and how deadly hitting your head with the trunk door is. Most importantly, they let you pipe your own music into the car radio by pointing the game to a folder where your MP3’s live (at least on PC). I was a little afraid that I would overplay the music in my time, and I would have welcomed being able to dilute the radio set with my own stuff.

The game also is scored with a great electronic/orchestral OST by Wilbert Roget as well, but it is sadly hard to notice with the somewhat overpowering presence of the car radio. I wish it was a little more aggressive in playing when on foot, but so it goes.

The car radio is ironically the unsung best feature of the game. The songs they licensed to play are great, and they interact in surprising ways in reaction to the anomalies you may encounter. Some may add static, some may distort time, and you learn the difference and their meaning quickly. If you hit certain anomalies and the car is malfunctioning, there is a good chance an absolutely unhinged radio show might play. One that springs to mind is… someone describing how to make a soup out of non-edible materials.

I could talk about Pacific Drive forever, but really, it is meant to be played. It is available on the PS4, PS5, and PC. The PC requirements are kind of high to get the full effect, it takes power to lovingly render an Oregon forest at 60MPH, but it can be chopped down to size if need be.

I may have left the Olympia Exclusion Zone, but I will never escape the Olympia Exclusion Zone.